From the Archives ...

Trout tips - from tackle shops

Presented from Issue 105, August 2013

We did a bit of a runaround Tasmania’s tackle stores to see what their tips for the first month or so of the tackle season were. We asked what the top three places to fish were, plus lures, flies, baits and a few other things.

Here is a rundown on their answers Whenever, and wherever you fish - anywhere, or for any fish in the world - ask the locals and especially ask at the local tackle store. They know what was caught today, yesterday and on what.

Please check all relevant authorities before fishing - www.ifs.tas.gov.au and dpipwe.tas.gov.au . Don't forget issuu.com/stevenspublishing for years of back issues !

Return to Rowallan

It had been over 16 years since I last fished Lake Rowallan. As a young man growing up in the rural community of Deloraine, it was a lake reasonably close to home and where I spent many a night camped on its shorelines. My last trip there was 14 December 1994. I remember this as I have a picture of a 14 pound brown trout on my lounge room wall with that date on the plaque. It is my biggest ever trout and the memories of that catch remain with me as if it were yesterday. To see a fish of that size come out of Rowallan’s light tannin coloured depths was something I will never forget but as I was a bit of a “scallywag” in those days, and I won’t elaborate on that, it was a reward that to this day…. I hardly felt that I had earn’t. Many things have changed since then, the most notable is the outlook and respect I now possess for our fisheries and those charged with looking after them. Anyway, with this all in mind, I decided to hook on the trailer, grab a couple of mates and head back for a day’s fishing at a lake that I seemed to have forgotten about . Why it’s been so long between drinks I cannot answer, perhaps it’s just another one of those lakes that are largely forgotten about… and I don’t know why. It is a lake close to many of our major population areas, yet seems to fly under the radar of most of the State’s freshwater anglers. In fact I would go so far as to say that many wouldn’t even know where it is. It is well stocked, has some absolute monsters in it and is very easily accessed, especially to those living in Tasmania’s North and North West. You hardly ever hear of any fishing reports coming from it and those that do fish it on a regular basis seem to like to keep it that way.

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Other Lakes

- Hits: 7985

Easy Day On The water

Jim Schofield, Steven Hambleton and I had made an early start to the day with a dawn run on the wind lane feeders on Great Lake. As the morning progressed and the midge feeders disappeared we moved onto some boat polaroiding. There was a northeasterly wind blowing as we punched our way into chop from Swan Bay towards the southern side of Howells Neck Island. The water level of Great Lake had dropped so much that Howells Neck Island was no longer an island and was more like an extension of Elizabeth Bay. As we moved into the shallows, fish were spotted almost immediately. Big buggy Chernobyl Ants, Red Tags and stick caddis all took fish. Further along the shore the wind was blowing into the shoreline stirring up the water along its edge. A closer look saw fish appear and then disappear in amongst this band of discoloured water. The fish were also patrolling the clearer less turbulent water. A single hookup quickly turned into a double hook up, then a triple hookup as all three of us made the most of a steady run of fish as the boat continued to drift down this productive shore. Fish numbers started to drop off, as the features of the lake started to change. In an attempt to seek out similar water we crossed over to the western side of the lake into Canal Bay. With the wind and sun at our back we drifted in and along the southern shore. Conditions were perfect, with blue skies and a light wind to conceal our presence, we had fish swimming right up to within a couple of metres of the boat before they would spook. It was just one of those days when everything came together. We stayed for the evening rise in Swan Bay as usual, before finally calling it a day. We had fished from dawn to dusk and had done it all from the comfort of Jim’s mobile viewing platform. Far too civilized for me, now where are those walking boots!

Craig Rist

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Great Lake

- Hits: 5124

Surface lures For Trout Fishing

The surface is just about the most fun you can have as an angler. Whether chasing giant trevally in the coral sea, bream in the estuaries, or dry flying trout here in Tassie you can’t help but get excited watching something come up and slurp or smash your top-water offering. Although they have been around for many years, surface hardbodies for trout have never really hit a spotlight but with the new methods and gear being developed at the moment it’s only a matter of time before people begin to look more seriously at top-water options. It takes some time to perfect your technique but it is essentially easy to get started and can be a very effective tool in your trout fishing arsenal.

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Trout Fishing

- Hits: 11338

Meet the Flatheads

How many Flathead are caught in Tassie? Flathead are the most commonly caught recreational species in Tasmania, accounting for almost two-thirds of all fish caught. Over 1.8 million flathead were caught by Tasmanian recreational fishers between December 2007 and November 2008. 1.07 million of these flathead were kept and 745 000 (around 40%) were released, showing an increasing trend toward fishers doing the right thing by releasing undersize fish.

Interesting Flattie Facts

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Saltwater and Estuary Fishing

- Hits: 13379

Jan’s Flies

Come in spinner that’s what all the fly fishing people are waiting for—the spinner hatches of spring time. On the rivers it will happen through October sometimes, it’s mostly dependent on the weather it’s those balmy mild spring days with little or no wind that’s required. On the highland lakes the first to be seen are normally a month later and for the past two seasons it has been so good one is not sure where to go first. So October and November are fairly well booked for me it will be mostly shore based fishing on the lowland rivers and highland lakes. Mid to late morning on the rivers and on a really good day the hatch can go on till late afternoon mind you that’s the rarity not the norm. Highland lakes spinner hatches are a little different in I like a slight breeze pushing off shore that’s to carry the spinners out onto deep water then better fish will hopefully feed. River fish will mostly work a beat. They will cover a few metres and disappear for a short time and then reappear and start the beat again. Stillwater fish will rise spasmodically so keep a sharp eye on the rise and try and judge which way the fish will head taking note where the fishes head is. This will mostly give the direction. Place the fly out in front so the fish will come upon it. My spinner patterns are fairly simple both red and black. Black Spinner Hook – Finewire size 14 12 10 Thread – Black Tail – Black cock fibres Rib – Very fine silver or copper wire Hackle – Black cock hackle Red Spinner Hook – Finewire size 12 10 Thread – Orange Tail – Black cock fibres Rib – Silverwire Head – One fine peacock herl Hackle – Red cock hackle Method for red spinner 1. Place hook in vice 2. Starting at the eye end take the thread the full length of the shank 3. Place a small bunch of cock fibres on top of rear end of shank tie down firmly and cut excess fibres away 4. Tie in rib and take thread two thirds of the way toward the eye now bring rib forward with nice even turns to where the thread is hanging cut away excess rib 5. Take one fine peacock herl and tie in cut away excess herl. Tie in hackle and wind forward toward eye making a nice tight hackle cut away any excess hackle 6. With the fine peacock herl wind it through the hackle try not to crush the hackle too much cut away excess peacock herl 7. Whip finish cut thread away and varnish The black spinner is tied the same but omit the peacock herl. Call 1300 787 060 Express

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Jan’s Flies

- Hits: 3505

Leaders and Tippets

When it comes to catching a fish on a fly, there is one section of the fly fishing system up which is of utmost importance. The balance needs to be right to present the fly, it needs to be fine enough not inhibit the swim of the fly and also not arouse suspicion in the trout, yet it needs to be strong enough to hold the fish once hooked and withstand fraying and ware and tear from the fish, rocks and other external influences. The leader really is the business end of a fly fishing system, and yes, it can be a complex business, yet one does not need to be a science degree to have a few set ups which will cover most fishing situations. The myriad of leader materials, diameters, breaking strains and set ups can be broken down, lakes or rivers some common principle apply and they can be used as a template to success. Traditionally leaders were made of silk and were given an X factor for the diameter of the gut. With the advent of modern materials such as nylon and tapered knotless leaders the X factor now generally refers to the diameter of the tippet of the tapered leader, or the general diameter rating of a particular material. (Although most spools now refer to diameter in decimal points of inches or millimetres). The attached table is a general guides to diameters and breaking strain. It still varies between the thousands of materials available, but works well as a general guide.

Apples and Apples

How often to you hear people make a statement like ‘this 8lb would pull a 4wd out of a bog’ when referring to their favourite leader material. The leader may be packaged as 8lb, but the diameter is really the point to consider. As you can see with both materials, there can be a large variance in diameter for a matching breaking strain. So the 8lb which ‘pulls your 4wd out of a bog’ may not be quite the product you think if it is compared to a truly comparable product of equal diameter.

LEADERS

Straight Leaders LAKE: On a fair day, with a nice gentle breeze at your back, a leader can be as simple as a straight piece of monofilament or fluorocarbon straight to the fly. Presentation and turnover of the fly are all but assured as the wind will aid in this and straighten out the leader for you. One of the basic principles of drift fishing in a boat is that you are always fishing down or down and slightly across the wind. Loch Style leaders are generally designed with straight monofilament or fluorocarbon for this reason. Multiple droppers, up to 6 or even 8 flies on a cast can be tied on a loch style straight leader, although a maximum of 3 flies is permitted in Tasmania. The diameter / breaking strain you select should match the size of your quarry, and the likely wear issues you will face while fishing. A simple leader for Tasmanian boat fishing is 15ft with 2 droppers no longer than 300mm and no shorter than 100mm in length. From the fly line the leader is 3ft (90cm) to the first dropper, then 5ft (1.5m) to the next and 5ft (1.5m) to the point. RIVER: Short line or Czech Nymphing at its basic form only requires a 6ft (1.8m) leader with two flies. Once again a level leader can be used, in the diameter appropriate to your quarry and conditions, and it is simply 4ft (1.2m) to the first fly and 2ft (600mm) to the point. As a short leader is being fished, turn over even with heavy nymphs is easy as they are basically lobbed with an open short cast. A three fly leader can be used for this technique by adding a third fly on a further 600mm from the point, and making a dropper where the point used to be. Droppers for these set ups should be between 100mm & 150mm long.

Tapered Leaders

The tapering leader is where the world can get complicated. The mechanics of a tapered leader relate to an even transfer of power from the fly line through the leader to the fly /flies on the tippet. Of course there are so many variables and external influences in the weather and conditions we fish in that no one size ever fits all. Tapered leaders are used for delicate presentation of flies, for casting into and across wind, for presenting to spooky fish that require a long leader. Of course the level leaders I have already detailed can also have a taper added to them to assist in turn over if conditions are less than ideal, this is done by simply using a thicker butt section to commence the leader. Pascal Cognard, the French triple world champion varies his leaders according to set formulas for windy and still conditions. The digressive leader clearly has a longer, heavier butt section to aid turnover of the fly in windy conditions, while the progressive leader has a longer more even taper throughout ensuring a smooth transfer of energy when there is less resistance from the wind. Fortunately we mere mortals have factory tapered leaders available to us; the point to take is that a factory leader can be easily modified to present a similar progressive or digressive leader depending on the conditions on the day. You do not have to buy different length leaders, just a few spools of varying diameter tippet and a little thought and experimentation will see you right. If conditions are windy, modify the leader with heavier and shorter tippet sections to aid turn over, and if it is calm, finer and more even sections can be added before the tippet section is added. The important thing is to graduate down and not go from a thick butt directly to a fine tippet, a surprisingly common mistake.

Fluorocarbon and Monofilament.

There is an endless argument and everyone has their own opinion about which is best and why they should be used this way or that. I can only put my spin on this argument here and hope it helps in your own decision making. Looking at the first chart it is quickly apparent that for a given diameter copolymers are stronger in breaking strain than fluorocarbons, so at first glance it would seem a no brainer to then use copolymer for most applications. However both copolymer and fluorocarbon have their strengths and weaknesses. Copolymers are supple and strong for their diameter. I choose to use these for dry fly and for light nymphing for smaller trout where small nymphs can be presented delicately. I particularly use fine copolymers for single dry fly on rivers where a very fine tippet can be fished with a small dry fly #16 - #20. Last season I caught a brown trout in excess of 3lb on the South Esk River with 0.12 mm, 3.6lb (1.8kg) copolymer tippet on a #16 Quill Body Spinner. This fish was under willows on the far bank and caused merry hell once hooked, but side strained out from under the willows and then kept out of the weed with a high rod, the tippet was more than ample. For dry fly on lakes with multiple fly rigs, I still use copolymer, however I use a less supple brand as droppers can twist badly with a very fine/supple material when long casting. If fishing a single fly on a lake I will revert to the finer, more supple brand of copolymer. Fluorocarbon really comes into its own lake fishing with lures, and where abrasion resistance is needed. Heavy fluorocarbon .22mm (around 10lb) can be used for lure fishing even on bright days. Using bead head lures counteracts the stiffness of the material will not affect how the lures swim and the diameter does not show up to fish, lighter fluorocarbon is required for smaller wet flies such as nymphs. The general ‘toothiness’ of trout on lakes takes its toll on tippet material and a thicker diameter and general toughness of fluorocarbon which can have its benefits when sub surface fishing on lakes. Occasionally I will use fluorocarbon on rivers where there are larger fish or there are particularly abrasive rocks such as pumice, but generally I prefer copolymer due to its suppleness allowing nymphs to move more naturally and dries to be presented on finer tippets. Fluorocarbon tapered leaders are hellishly expensive and the general consensus is that fluorocarbon and monofilaments do not tie well together. Generally this is rule is right, however if you intend to join a monofilament tapered leader to fluorocarbon, do it with heavier fluorocarbon around .22mm or .25mm. At these diameters a sturdy knot can be tied, which will hold better than a lighter tippet. Whatever you decide to do with leaders and tippet materials, a few simple rules will see you be able to make good leaders which can be fished effectively in many conditions. • Don’t buy materials based on breaking strain alone; compare diameters to make sure you are comparing apples with apples. • Think about whether you want a supple (being fine diameter and soft) or stiff (being relatively strong and abrasion resistant). • Shorten overall leader length and make a ‘steeper’ taper for windy conditions. • Likewise graduate the taper for smoother, better presentations is calm weather. With a bit of thought about what you want to achieve, making a leader to suit the conditions will make bringing that awkward trout undone all the more pleasurable. Likewise keeping a leader simple and easy will also save frustration and time when all you intend to do is fish down the wind. After all it’s only a simple fish you are trying to catch! Pascal COGNARD 5.75m nymphing leader Filament Length in cm Diameter - mm digressive progressive 0.45 75 45 0.40 65 50 0.35 55 55 0.30 45 60 0.25 35 65 0.20 50 50 0.15 50 20 0.08 – 0.12 200 200 Pascal COGNARD 5.75m nymphing leader *Source Czech Nymph and other Related fly fishing methods. X rating Diameter – inches Diameter – Millimetres Breaking strain Fluorocarbon Breaking strain Stroft Copolymer 8X .003 inch .10mm 1.4lb 2.2lb 7X .004 inch .12mm 2.6lb 3.9lb 6X .005 inch .14mm 3.2lb 4.8lb 5X .006 inch .16mm 4.7lb 6.6lb 4X .007 inch .18mm 6.2lb 7.9lb 3X .008 inch .20mm 7.8lb 8.6lb 2X .009 inch .22mm 9.8lb 11.3lb 1X .010 inch .25mm 11.2lb 14.2lb 0X .011 inch .28mm 12.9lb 16.2lb Note – Fluorocarbon in particular can vary enormously for given diameters, so check your own brand against this table. Brand Breaking Strain Diameter Stroft Copolymer 7.9lb 0.18mm Maxima 8lb 0.25mm Airflo Ultra Strong 8lb 0.205mm Scientific Anglers 8.8lb 0.20mm Copolymer / Monofilament Brand Diameter Breaking Strain Fulling Mill 0.255 8lb Riverge Grand Max 0.21 9.5lb Scientific Anglers 0.20mm 8.6lb Sight Free 0.21mm 8lb Fluorocarbons

Joe Riley

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Fly Fishing

- Hits: 7429

More on whitebait - From 1961

An extract from the Inland Fisheries Commission Annual Report 1961. Introduction In 1941, commercial exploitation began of the whitebait, Loverria sealii (Johnston).earlier the whitebait had been valued by anglers, who considered that the entry of great quantities of these small fish into the estuaries of rivers on the North- West and Northern Coasts, particularly from August to October, both provided a bountiful source of food for trout (Salmo trutta) and induced the trout to come into areas where they became more available to anglers. Dr M Blackburn of the CSRIO Division of Fisheries, in reports supplied to the Fisheries Division of the Department of Agriculture in 1948 and again in 1949, described the biology was followed by a sharp and substantial decline. A report of Dr Blackburn’s investigations was published in 1950 (Aust. J Mar. Freshw. Res. 1:155-98). Representations by the North-Western Fisheries Association and the former Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries Commissioners south the prohibition of further commercial exploitation of whitebait in the north and were referred to the writer by the Hon. Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries.

The Fish

The published reports show that the whitebait enter from the sea in spring for the purpose of spawning near the upstream limits of tidal waters, the fish are one year old and about two inches long. From 100 to 200 eggs are laid and adhere to submerged logs, stones, &c. Few adults survive for long after spawning. Eggs hatch in about three weeks and the young drift out to sea. Dr Blackburn fund that the whitebait of the Northern rivers belonged to a common stock which should be treated as one for purposes of management. Similarly there was another common stock in the Southern rivers. The Northern fish, when taken, are of higher quality because they comprise mainly gravid and unpigmented fish. The Southern fish, as taken, comprise of a higher proportion of darker, spent fish.

Fishing Methods

Tidal reaches of the two main Southern rivers, the Huon and the Derwent, are so broad and deep that effective netting with permitted apparatus is difficult, expect above the areas where the main spawning presumably takes place. Most of the Northern whitebaiting rivers have steep gradients to near the coast and have very short tidal reaches. Fishing is permitted by licensees only and is at present restricted to the months of August to December. A licensee may use up to four scoop nets, being not more than 30 inches in diameter at the mouth, nor more than five feet in depth. Such scoops may be fished as dip nets in the margins or as set nets with mouths facing downstream in the assumed path of fish in deeper water. At the peak of fishing activity which occurred in 1947, over 900 scoops were in use on Northern Rivers. Many such rivers are small and leads followed by fish could be almost completely blocked by scoops. If the fish tend to “see-saw” with the tide, or to drop back and return again as rain affects stream levels, the same fish might hae to pass and repass successive batteries of nets. The impracticability of marking such small fish makes it impossible to determine the precise movements of fish after entry and the extent of the escapement during the season. The catches for successive months in 1960 showed that over a third of the total was taken in August, approaching half in September and that thereafter quantities fell rapidly and were only about 3% after October.

Value of the Fishery

At the peak of production in 1947, when the yield of Northern rivers was about 30 times as great as in recent years, the wholesale value of each catch was only £16,000. Canneries took much of the catch. The Tasmanian whitebait has never achieved the special fish delicacy value of the New Zealand whitebait, which fetches several times the price. (The New Zealand Commercial whitebait comprises mainly larval Galaxias attenuatus, a species which, although present in Tasmania, is not sufficiently abundant here to support a fishery). The recent retail price of Tasmanian whitebait has been about 2s. 6d. a pound. Whitebaiting is not a traditional fishery of the kind that has lead to the construction of jetties and other capital assets. A licensee can equip himself for a very small sum, although in paces a rowboat is also desirable. It is not like an ordinary fishery, where the necessity for a substantial capital outlay can condition the rate of expansion. With the whitebait fishery, any appreciable improvement in runs of fish could be followed within a week by a sharp increase in the number of persons equipped with licences and scoops. At its peak, whitebaiting provided direct part or full time seasonal employment for about 230 persons – a number which has declined to about 65. Except for a very few professional fisherman, who would apply themselves to whitebait or other species, according to abundance and ruling prices, the fishing is carried out largely as a spare-time occupation by amateurs having other means of livelihood, or by pensioners. At its former peak, the fiery is said to have had a disturbing effect on regular employment. It has never been dependable and sole source of livelihood. The average earnings of whitebaiters, even at the 1947 peak, were only about £70, earned over a season of several months. In 1960, wen the total catch was a little better than in any of the previous five years, individual fisherman still took on an average only a sixth the quantity they took in 1947.

Destruction of the Whitebait Fishery

Although commercial whitebaiting had commenced a little earlier in the South, there was only slight activity in the North before 1943. Then the number of licenses increased about four-fold from 1944 to 1947. The peak in total production in 1947, a year which there was a 38% increase over the 1946 catch, yet a drop in yield per scoop, or fishing unit of about 27%. Data published by Dr Blackburn for the 1943-1948 seasons have been amplified by further records made available by the Secretary of the Fisheries Division of the Department of Agriculture. The number of rivers fished rose from three in 1943 to seven in 1945 and a maximum of eleven in 1947. The Mersey and the Leven each contributed to about one third of the total catch. The 1960 the number of rivers fished had fallen to eight and in the Inglis, Cam and Blythe the catch was less than 150 lb. each. The Leven and Mersey produced over three-quarters of the total, the balance coming from the Duck, Black and Rubicon. The drop in catch per scoop from 1550 lb. in 1946 to 1130 lb. in 1947 might have been attributable to competition between the increased number of fishing units employed in restricted areas. However, no such explanation could account the catastrophic fall in 1948 of both gross yield and catch per unit. Dr Blackburn, in supplement to his 1948 report, proposed a total closure in 1949, to be followed by catch quotas of 100 tons in 1950 and 200 tons in 1951 with continuing observations to learn the most satisfactory permanent level. In consequence, there was no open season in 1949 and the Sea Fisheries Advisory Board decided to be advised by Dr Blackburn on a suitable duration for the 1950 season. Thereafter, regulations were drafted by providing for an open season from 15th August to 30th November, with machinery provisions for earlier closure to be ordered by Gazette notice, should the proposed quota be reached earlier. When the proposals became known, there was strong opposition from canners to the suggested quota of 100 tons. Following discussions between their representatives and the Sea Fisheries Advisory Board, it was decided the quota for 1950 should be 375 tons. Such a quota amounted to a greater quantity than had been taken in any earlier year except one and was actually 80% greater than the average annual catch f 209 tons for the years 1943-1948, which has caused the collapse of the fishery. A reservation that if “upon examination, any signs of depletion are indicated, the Minister will take action…to terminate the season” was meaningless, in view of the notification to the canners at the same time of this high quota. Obviously, if 375 tons had been taken, it would have proved an abundance of fish. But until such a quota was reached, the canners could argue that the run was late and they were holding cases, tinplate, labels &c., which they should be permitted to use. (The word “quota” was not in fact used in the notification to canners, which referred, not to a maximum, but “optimum” catch). In fact, no action was taken at all under the provisions for terminating the season, although in 1950 the catch fell to 10% of that of 1947 and when thereafter the deterioration continued until, in this last five years, the average annual yield has been 12 tons, that is, about one thirteenth of the proposed quota, the catch per unit in the last two years has averaged 130 lb. as against 440 in 1948 and 1550 in 1946. Since 1950, changes in regulations have ad the effect of making still more effective the destruction of the remnants of the Northern whitebait population. (For other reasons that whitebait conservation the Forth was closed to whitebaiting, but its earlier contribution had amounted to only 4% of the total yield). The 1950 regulations prohibited the taking of whitebait between sunset on Fridays and sunrise on Mondays. This reservation was dropped in the 1957 regulations. The earlier regulations prescribed a closed seasons from 1st December to 14th August. The 1957 regulations provided for an open season from 1st August until 1st January. The extension by four weeks at the end is unimportant, as the run is greatly reduced by the end of October, but the addition of a fortnight in August materially reduced the period within which uninterrupted spawning had previously been possible. In 1960, over a third of the total catch was taken in August and summaries of monthly catches indicate the probability of appreciable runs occurring in July. Probably this pre-season entry is all that saved the stock from extermination, or delayed such a happening.

Trout and Whitebait

If trout had never been established in the Northern rivers and coastal waters of Tasmania, there would still be adequate justification for a total cessation of whitebaiting for a number of years to learn whether it is not still possible for this species to re-establish itself in sufficient strength to permit carefully regulated exploitation at some future time. However, as was learnt in 1949, when whitebait were very greatly more abundant than now, closure for a single season is quite inadequate to permit recovery. Whatever influence the introduction of trout may have had on the whitebait population, the facts are that the two species co-existed with a considerable overlapping range for nearly 80 years and that predation by the trout was never severe enough to precent the whitebait continuing in very great abundance. Dr A G Nicholls, in a general consideration of size and abundance of trout in fresh and tidal portions of Northern rivers, between 1945 and 1954, (Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. Vol 9, 1, 19-59) made no direct observations on the food of trout or special enquiry into inter-relationships of trout and whitebait. However, he remarks that he did not find any “direct, consistent correlation” between the estuarine trout fishery and the commercial whitebait fishery. It is important that this statement should not be misconstructed as a statement that the estuarine trout fishery was not in any appreciable measure influenced by the abundance of whitebait or the whitebait fishing practice. Direct and consistent correlations are unlikely to be demonstrated by the relatively scanty data, especially when there is only a partial environment overlap and the predator species is very catholic in its feeding habits. Indeed, Dr Nicholls has been careful to how the abundance of whitebait could affect the availability of trout to anglers by bringing them into effective rand of shore-based anglers. He also demonstrated that the number of days devoted to angling in tidal waters by the typical angler dropped by half as the whitebait stocks fell off. The finding that such anglers as did fish tidal waters took much the same quantity of fish as formerly is not inconsistent. While there is no positive evidence that it is so, it is a logical and widely held belief that trout, which are present in abundance in coastal waters, follow shoals of small anadromous fishes into rivers and that the duration of their stay in tidal reaches is much dependent on the continued availability there of such small fry. Whether this is correct or whether the presence of concentrations of whitebait in marginal waters simply induces local inshore movement of trout, which would normally be lying deeper and more widely dispersed in the estuaries, is it not really important. It is beyond reasonable dispute that the presence of whitebait does induce trout to feed both vigorously and conspicuously at inshore points where the small fry concentrate and that thereby trout become readily available to anglers. Such concentration points (usually eddies offering some shelter from strong currents) appeal equally to whitebaiters and to trout. As the angler seeks the actively feeding trout, he comes into direct positional conflict with the whitebaiter. In the restricted estuaries of the Northern rivers, each with its limited number of good concentration points, the actual disturbance or domination of areas by whitebaiters can make angling relatively ineffectual, or, at the very least, very unattractive. To the angler, the whitebaiter is a source of direct interference with his sport, while the whitebaiter, I turn, suffers the annoyance of having the smooth movement of whitebait frequently disturbed by the feeding trout. No one who has observed trout feeding on whitebait would need to have his observations reinforced by analysis of gut contents, before and after the commercial whitebait fishery developed, to be convinces that the substantial destruction of the whitebait population has been seriously damaging to the trout fishery.

Conclusions

1. An indigenous species of fish, the whitebait, which a few year back was enormously abundant, has so diminished in numbers that recent commercial yield has been about 6% of what it formerly was.

2. Trout and whitebait had co-existed for nearly 80 years and the whitebait continued to be extraordinarily abundant until commercial exploitation started.

3. There is irrefutable evidence that the whitebait fishery has been substantially destroyed by gross over-fishing, which has continued, with increasing ill effects, for a decade after competent scientific enquiry had diagnosed the cause of the first sharp decline and recommended remedial measures. There has for 10 years been failure to attempt to arrest or remedy the continuing decline by exercising powers provided for that purpose in regulations made in 1950. Instead, the earlier regulations have been relaxed further to permit more sustained fishing during the former open season and an extension of such season.

4. The destruction of the Northern whitebait population may already have proceeded beyond the point from which recovery might be possible. Only the immediate and complete cessation of all exploitation in Northern waters for some years would appear to offer any hope of saving the whitebait population.

5. An incidental effect on the substantial destruction of the whitebait population has been the loss of a valued trout food. Such food has been of special significance in that it greatly increased the availability of trout in estuarine waters, thereby making for better fishing and less congestion in inland waters.

6. Whitebait fishing in the Northern rivers is the part-time interest of 65 persons. Trout fishing in the same rivers is the part-time interest of over 6500 local North-West Coast residents.

Recommendations

1. It is recommended that regulation 33 (3) of the 1957 Sea Fisheries Regulations be invoked at once and that a Gazette notice be issued closing all the Northern rivers to whitebaiting in the season which otherwise would be open on 1st August next.

2. That in view f the failure of the single closed season in 1949, to permit recovery of the stock, which was then in a very greatly stronger position, closure for a number of years now be contemplated. DF Hobbs, Commissioner. 30th June, 1961.

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Whitebait

- Hits: 5101

Sea Trout are a bit of an enigma around the world. Runs of these brown trout, born in a river, migrating to sea, and returning to a river for feeding (or spawning in autumn), are notoriously hard to predict. But like searching for Lasseters mythical reef of gold, the thrill of the chase and the promise of big rewards (sight-fishing to double figure fish if successful), offers more than enough attraction for most of us fly fishers! Timing is all about recent rainfalls (the time between the wet of spring and the dry of summer is when things peak), and the availability of migratory food sources such as whitebait are key to success.

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Saltwater and Estuary Fishing

- Hits: 3494

Carp in Lake Sorell

For many southern anglers Lake Sorell has been one of the most popular, accessible and productive brown trout fisheries. Its shores were home to private shacks, club shacks, and hundreds of campers.

That is until the sudden infestation of carp, a problem that continues to plague this water. Despite continuing efforts since 1995 by the Inland Fisheries Service to eradicate the pest, the Spring of 2009 saw an increase in juvenile carp which, according to IFS Director, John Diggle, was “the biggest spawning event we have had.”

It is estimated that around 5,000 carp are now swimming around Lake Sorell where as prior to last year’s spawning, numbers were less than 50.

According to the Director, “The good thing is that these fish are all juveniles and as they are unable to breed for a couple of years we have a window of opportunity to wipe them out.”

IFS staff have already taken out over 14,000 carp from Lake Sorell last summer, and it is vital to eradicate mature carp as soon as possible as a four kilogram carp has the potential to lay one million eggs.

John Diggle believes Lake Crescent is now free of carp and that, in itself, is quite an achievement. No juveniles have been found since 2000, and no adult females have been detected for nearly three years. According to Diggle, “It is a clear demonstration that we can and will eradicate carp from Lake Sorell.”

Although carp do eat some macro-invertebrate species that brown trout also enjoy, they are not predators of trout fry or fingerlings. The issue is what carp can do to the food chain and to the water quality.

Compounding the presence of carp in Lake Sorell is the issue of poor water quality resulting from drought conditions. This is also impacting on Lake Crescent. Both waters have high levels of turbidity – colloidal particles in suspension which don’t settle to the bottom of the lake bed. According to Diggle, “It’s a bit like a farm dam that doesn’t clear, and that just isn’t attractive to anglers.”

Whilst this is a result of drought conditions in this part of the island, low water levels back in 2000 also contributed, especially in Lake Sorell where there has been some erosion of the lake bed.

Currently the water management plan for the Clyde catchment area is under review, and there will obviously be some discussion around critical minimum water levels necessary to sustain both trout fisheries, and especially for the protection of Golden Galaxias in Lake Crescent. No doubt other stakeholders – irrigators and local town water supplies – will be seeking their share of the resource. But there is no doubt that the IFS is putting a strong case for critical minimum water levels so that this fishery can once again be a prime destination for trout anglers.

If water levels can be sustained, the carp eradicated, and water turbidity controlled there is no reason why Lake Sorell can’t regain its former status as one of the state’s top fisheries which used to attract 50% of the state’s anglers in any one season. Afterall, there is a very good head of fish in Sorell resulting from excellent natural spawning conditions, albeit dependent upon variable rainfall patterns.

According to the IFS Director, “That’s what I want … that’s what I have been working on for years. However, our problem may not be so much about carp or water quality but climate change. If the things people are saying about climate change are true, and it is only going to get drier than we are now, the future may not so promising for either lake, or for most of the eastern part of the island.”

Then again, Lake Dulverton is now full and has been stocked; Tooms Lake is spilling and has also been stocked; and Craigbourne Dam should again deliver angling delights for southern family expeditions to this water.

So it looks like at least two years before Lake Sorell will again be open for anglers, although the IFS will assess the situation at the end of each summer.

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Lake Sorell

- Hits: 5309

Sea run trout tactics – Craig Vertigan

During the trout off-season I tend to spend a bit of time chasing bream, to continue getting a fishing fix, and spend time tying flies and dreaming about the trout season to come. It’s a time to spend doing tackle maintenance, stocking up on lures and dreaming up new challenges and goals for the trout season ahead. When the new season comes around I usually spend the first few months targeting sea runners. Sea run trout are simply brown trout that spend much of there lives out to sea and come in to the estuaries for spawning and to feed on whitebait and the other small endemic fishes that spawn in late winter through spring. Mixed in with the silvery sea runners you can also expect to catch resident fish that have the typical dark colours of a normal brown trout as well as atlantic salmon in some of our estuaries that are located near salmon farm pens. Living in Hobart it is quick and easy to do a trip on the Huon or Derwent and is a more comfortable proposition compared to a trip up to the highlands with snow and freezing winds to contend with.

- Written by Stephen Smith - Rubicon Web and Technology Training

- Category: Saltwater and Estuary Fishing

- Hits: 18178

Subcategories

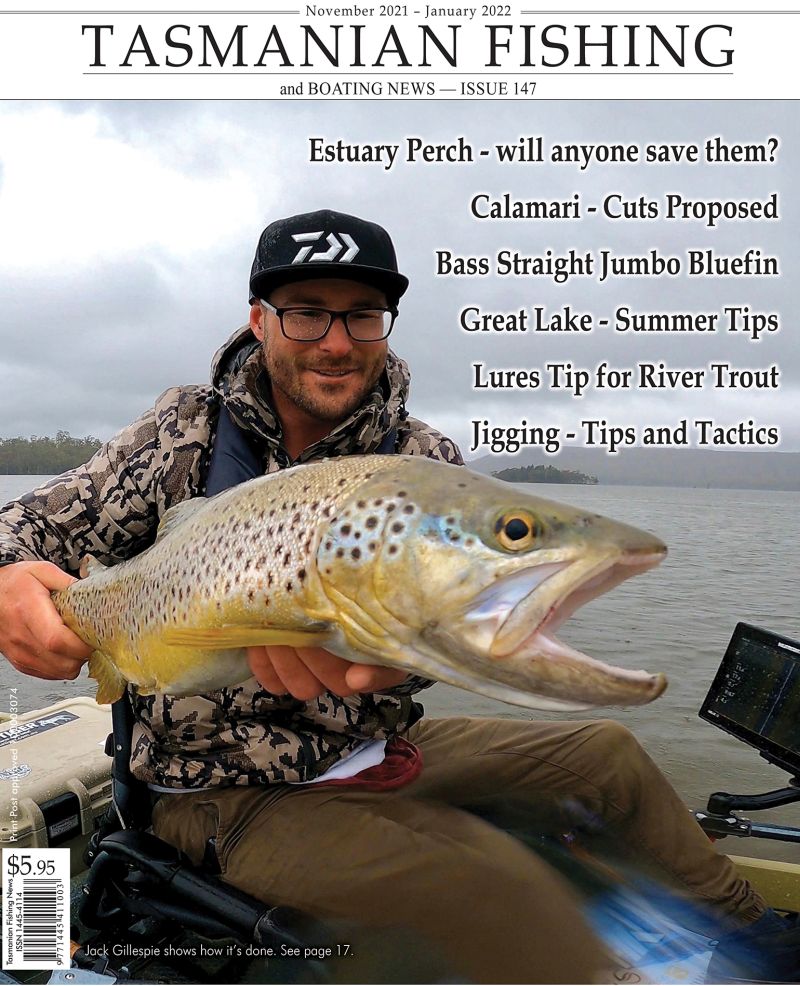

Current TFBN

Click above for current issue content. The current issue of TFBN is extensive and topical. In Tackle Stores, Newsagents and by subscription.

Delivered to your door for $48 for 2 years (8 issues). To subscribe, send Mike $48 via www.paypal.com.au . (Basic instructions are here) The email is at Contact Us. Your address will be included from PayPal.

Or phone Mike with your c/c handy on 0418129949

Please ensure your details are correct, for Mike to organise delivery.

TFBN Newsletter Sign up Form

Why not submit an article ?

When you have finished for the day, why not have a brag about the ones that didn't get away! Send Mike an article on your fishing (Click here for contact details), and we'll get it published here. Have fun fishing - tasfish.com

Category Descriptions

Here is a list of all of the Article Categories. The number in Brackets, eg (13) is the number of articles. Click on Derwent River and all articles relating to the Derwent will be displayed in the central area.

Articles by Category

-

Rivers (3)

-

Saltwater and Estuary Fishing (149)

-

Kayak Fishing (34)

-

Lakes (1)

-

Great Lake (62)

-

Lake Leake (52)

-

Woods Lake (16)

-

Lake Augusta (11)

-

Huntsman Lake (13)

-

Lake Pedder and Gordon (10)

-

Lake Dulverton (5)

-

Lake Crescent (6)

-

Tooms Lake (10)

-

Lake Mackintosh (2)

-

Lake Barrington (5)

-

Little Lake (8)

-

Meadowbank Lake (5)

-

Lake King William (7)

-

Lake St Clair (2)

-

Western Lakes (12)

-

Arthurs Lake (35)

-

Lake Echo (7)

-

Four Springs (54)

-

Lake Sorell (7)

-

Lake Burbury (6)

-

Other Lakes (57)

-

Brushy Lagoon (18)

-

Little Pine Lagoon (5)

-

Penstock Lagoon (16)

-

Brumbys Creek (7)

-

-

Events (48)

-

Estuary Fishing (0)

-

Coastal Catches (46)

-

Super Trawler (46)

-

IFS, DPIPWE, MAST and Peak Bodies (435)

-

Commercial Interests (98)

-

Other (24)

-

TFBN Back Issues (8)

-

Fly Fishing (67)

-

Trout Fishing (252)

-

Meteorology and Weather (8)

-

Jan’s Flies (50)

-

Tuna Fishing and other Game Fishing (86)

-

Cooking Fish (19)

-

Fishing Information (1)

-

Fishing Books (8)

-

Videos (5)

-

Tackle, Boats and other Equipment (146)

-

World Fly Fishing Championship 2019 (2)

Popular Tags

windyty.com

Visit https://www.windyty.com/

Rubicon Web and Technology Training

Hello everyone, I thought it would be a good time to introduce myself.

My name is Stephen Smith and I have been managing the website tasfish.com since May 2009.

It has been an epic journey of learning and discovery and I am indebted to Mike Stevens for his help, support and patience.

I am developing a new venture Rubicon Web and Technology Training ( www.rwtt.com.au ). The focus is two part, to develop websites for individuals and small business and to train people to effectively use technology in their everyday lives.

Please contact me via www.rwtt.com.au/contact-me/ for further information - Stephen Smith.

From the Archives ... (last chance)

Sea Run Trout

Mid Sea-Run Season Report

Sea-run trout fishing this year got off to a cracking start in most areas, with the majority of anglers employing nearly every trout fishing technique to secure fish in local estuaries statewide.

Even those anglers fishing the "off-season" lower down in our estuaries for sea-trout commented on the number of fish moving in early August.