Presented from Issue 117, August 2015

Presented from Issue 117, August 2015

Dry fly or wet fly

I like catching fish on a dry fly just as much as the next person and will often persist with floating flies early in the season, experimenting to try for a response, . I know that I will get refusals and catch less doing this, but for me this is not a numbers game.

Success or failure with any fly can vary from water to water in the Western Lakes, as each location can be vastly different from the next. What fish feed on can change from lake to lake or from shore to shore depending on the make up of each lake, the food within it and the effects of rising or falling water levels. The trick is to find a fly and technique that will trigger a response from them more often than not. Sometimes it comes down to finding a single fish that is willing to take a chance and open and close its mouth onto a fly that vaguely resembles a potential feed.

Early season experiment

Last season I conducted one of my early seasons floating fly verses wet fly experiments with my good friend Mark Woodhall. Mark fishes the Western Lakes exclusively all season and has done this for most of his fishing life. Like me, Mark is not a numbers man and we can have a great day in the Western Lakes exploring new lakes and trying different techniques and flies, without worrying about blowing a few fish.

Mark and I began the day’s hike with the standard 4am departure from the car park, to arrive at first light. I started the morning with my Emerging Woolly Bugger fly which has a foam head and Hi–vis post. This fly floats with its foam head in the surface film with the rest of the fly submerged to resemble an injured or dying Galaxia. Mark decided to use a slow sinking fly, tying on a size 8 Gibson’s black and orange Woolly Bugger to fish it inert or stripped back depending on the mood of the fish and the weather conditions of the day. We split up to fish different bays for the start of the morning to make the most of the low light in the hope of finding tailing fish.

I sat on a bay for 15 minutes but saw nothing so I moved around to the next likely tailing shore to see a faint disturbance bulging the calm surface film, signaling the presence of a fish in the shallows. I made a cast well ahead of the disturbance and the fish responded immediately pushing up a bow wave over to my fly. I watched the fish swim up to the fly, turned away, then back for another look and then disappeared, obviously not happy with what it had seen. That wasn’t the response I was hoping for!

|

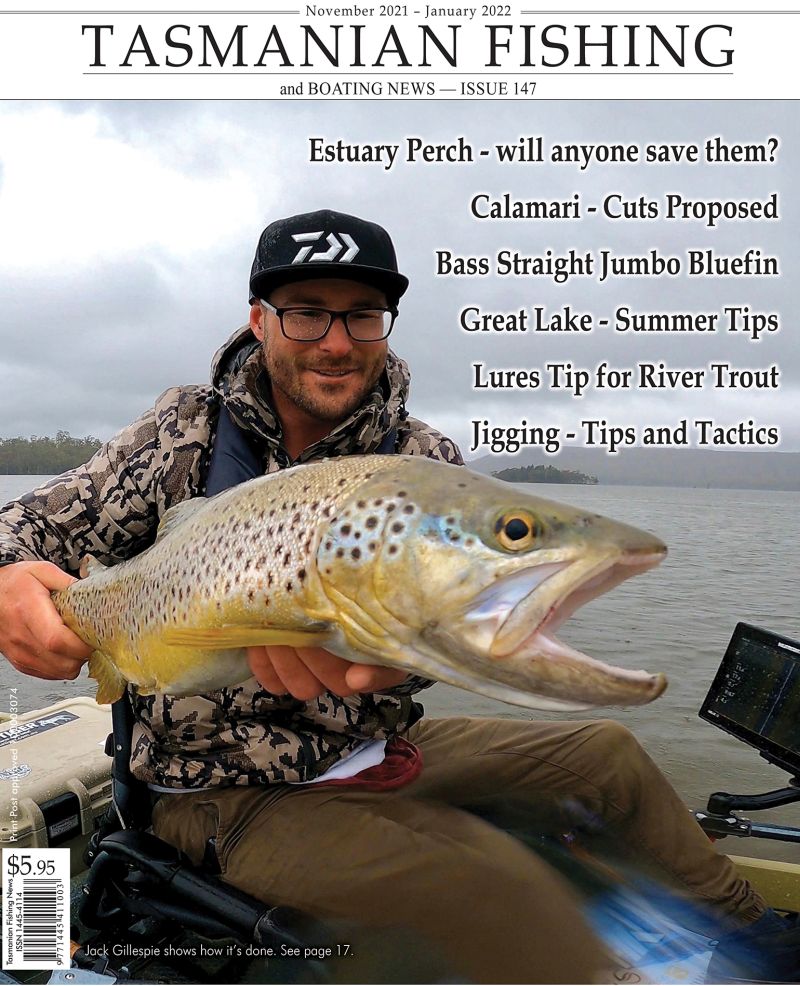

| The walk can be worth it. Craig Rist. |

I changed flies (possibly prematurely) to a size 10 foam Chernobyl type fly with brown rubber legs. Mark had caught up to me after exploring a few bays but hadn’t seen a fish. We continued along the shore looking for signs of fish. I spotted another tail and offered the cast to Mark but he wouldn’t have it and insisted I try the floater. I cast fly ahead of the fish which was now clearly visible swimming beneath the water in the late morning light. The fish swam within 20cm of the fly but didn’t identify my floating insect like fly as food and continued to swim along the shore. I picked up and dropped the fly in front of the fish again and gave it a twitch but again it swam past my fly. I urged Mark to quickly try his woolly bugger before the fish swims out into deeper water.

Mark made the cast, landing his fly a metre in front of the fish and allowed the wooly bugger to slowly sink as the fish approached. The fish swam straight up to Mark’s fly and ate it without hesitation. Mark lifted his rod to set the hook and had the fish thrashing wildly under the resistance of his rod until it changed tack and headed for deeper water. Mark lowered his rod to the side and turned the fish with some steady side strain making short work of what could have been a drawn out fight. Mark soon had a beautiful golden Western Lakes Brown, dripping from his hands for a quick photo and then a release.

I continued to persisted with a floating fly for a while until I finally succumbed to tying on a wet fly in the afternoon after Mark landed another fish on the Wooly Bugger. On this day, these fish just refused to lift their head for a floater and seamed to be fixated on a large baitfish fly like the Woolly Bugger. I wanted to confirm this by resisting the urge to go straight for a large woolly bugger and tied on a Montana nymph and presented it to the very next fish, which swam up to it and refused it. I changed flies again and the same thing happened to a small black fur fly. With less than an hour to go before we had to start walking out Mark tossed me one of his Gibson Woolly Buggers and walked ahead of me to find another fish for me to try it on. He had only walked a few metres when he yelled out, “I got another one here for you mate”.

The fish was lying in between two large submerged flat rocks facing away from us in a narrow little bay that was littered with large boulders jutting out of the water. For the fish to see my fly in the water I had to cast the fly into a gap about a metre wide between two submerged boulders that were 1½ metres beyond the fish that was still lying motionless in its rocky crevice. The Woolly Bugger hit the mark with a splat and slowly began to sink. The fish responded immediately and swam over to the fly and stopped with a flash of white from its mouth. That was all I was after and set the hook. The fish flapped around on the surface between the rocks and I held him there for as long as I could to get it to expel some energy.

This fish was carrying some weight and by the look of the width of its flanks as it was rolling at the surface it was pushing the five to six pound mark. What I thought was going to be an easy fight didn’t last long as it regained its senses and swam straight at me, then turned and swam around a large boulder that was sticking out above the water. I quickly released the drag on the reel and dropped the rod towards the fish to take the tension off the leader as it was being pulled around the boulder. At the same time I had jumped over some low-lying scrub to reposition myself above the boulder to get the line out and pressure back onto the fish before it had a chance to find a hole in amongst the rocks to berry its head. I the 4 weight fly rod buckling under the pressure as I pulled low and hard to regain the upper hand. As soon as I had some control I quickly steered the fish out from the confines’ of the boulders into open water and then into the bank where Mark kindly scuffed the fish by the tail and held on with a grin from ear to ear. This fish would certainly have pulled the scales down to six pounds and when it was lifted from the water it had a lovely green back with a magnificent coppery brown belly. It was a perfect example of a Western Lakes Brown and a nice way to end the experiment on a high.

Flies To Try

Flies To Try

Fur flies and Woolly Buggers in sizes 10, 8 or even 6 are proven early season flies that are very versatile in there application. Unweighted versions are really good for that inert presentation where you wait to see the mouth open and close or see the floating leader draw away before you set the hook. These flies are also great blind searching flies to use over submerged rocks and deep drop offs where lazy browns like to rest and seize any opportunity for an easy meal. Brass or tungsten beads tied in at the head of these flies a slight jugging action and additional weight to search those deep corners of the lake.

I like to use floating flies whenever I can just to see a trout rise to my fly. Floating flies that work early in the season usually represent a bait fish, tadpole, snail or beetle that is floating in the surface film, more like an emerging nymph fly than a traditional dry fly that sits high on the water. Traditional flies and your own creations that represent the diet of trout in the beginning of the season can be turned into floating flies simple by adding the right amount of foam or other floating material when they are being tied. If you tie your own flies this can be a fun and rewarding way to change the way a traditional wet fly can be fished.

Where To Start

The Western Lakes can be an unforgiving place to fish. The fish don’t come easy at this time of the year and the weather can be calm and warm one minute and brutally cold windy and wet the next. But for those of us who love to count the spots on their back as they hug the shoreline or see that tail in the shallows. It’s worth every footstep into this unique fishery. The great thing about this place is that it doesn’t take long to learn where fish are most likely going to be and the more time you spend back here the more you will learn and map out the fish holding structure of each lake. The numbers of fish in each lake also varies quite a lot and naturally increases or decreases your chances of finding fish.

Shallow weedy bays are an obvious choice to find tailing fish at dawn and dusk but fish will often leave these bays once the sun gets up. These fish often leave these very shallow bays and edges to prowl the deeper under cut banks or rocky ledges to find food or stop and hold up in these areas that provide both cover and a good ambush point. These stationary fish will predominantly be facing into wind and waves to hold position and to take advantage of anything edible that the wind and wave action pushes towards them. Knowing this makes the shoreline with the wind blowing into it very appealing and worth having the wind in your face to fish rocky drop offs and under cut banks. Many of these fish are so close to the bank that they are often caught within a leaders length of the rod tip. Fish that are cruising these edges can appear from nowhere as they swim in and out of the under cut banks, rocks and overhanging alpine scrub. Brown trout will move very slowly along these edges so it pays to stop and look for a few minutes before moving on.

When the weather conditions rule out site fishing all together and the water is very calm I like to fish a fly that sinks very slowly and fish it with an inert presentation while standing well back from the waters edge. The fly is delivered with a straight-line cast to stay in contact with the fly as it sinks. If a fish takes the fly as it is sinking the leader will suddenly draw away, signaling the time to set the hook. If there is no signs of a fish taking the fly as it sinks to the bottom I will slowly retrieve the fly all the way back to the shore before lifting the fly out for another cast further along the bank. This is a very effective way of bring undone those big sensitive fish that are often spooked by walking too close to the edge.

When the weather conditions rule out site fishing all together and the water is very calm I like to fish a fly that sinks very slowly and fish it with an inert presentation while standing well back from the waters edge. The fly is delivered with a straight-line cast to stay in contact with the fly as it sinks. If a fish takes the fly as it is sinking the leader will suddenly draw away, signaling the time to set the hook. If there is no signs of a fish taking the fly as it sinks to the bottom I will slowly retrieve the fly all the way back to the shore before lifting the fly out for another cast further along the bank. This is a very effective way of bring undone those big sensitive fish that are often spooked by walking too close to the edge.

Other places that are worth a cast are the areas of submerged rocks and weed beads that are well out from the shoreline. Creek mouths are also worth a few careful casts in close and it never hurts to sink a fly down beneath the branches of any low overhanging tree, alpine shrub or grasses. You just never know what might swim out and take a closer look at your fly. Over the years I’ve had plenty of blank days back in the Western Lakes but it’s the challenge and the memories of the good days that always seem to bring me back for more.

Craig Rist